TL;DR:

- Satlas, an innovative map, combines AI and satellite imagery to showcase worldwide renewable energy projects and tree coverage.

- Developed by the Allen Institute for AI, the map employs “Super-Resolution” technology for enhanced clarity.

- Renewable energy projects, including solar farms and wind turbines, are spotlighted alongside changing tree canopy coverage.

- Satlas offers policymakers and researchers invaluable insights to combat climate change and meet environmental goals.

- Despite impressive capabilities, the AI-powered map still grapples with accuracy issues and occasional “hallucinations.”

- The map was built upon extensive manual labeling of satellite images, training deep learning models to recognize key features.

- The Allen Institute plans to expand Satlas to provide maps revealing global crop types, aiding climate research.

Main AI News:

A groundbreaking revelation has emerged on the horizon of climate-conscious technology—a pioneering map encompassing both the expansive scope of renewable energy initiatives and the lush expanse of tree coverage across our planet. This avant-garde cartographic masterpiece, christened “Satlas,” has been ceremoniously unveiled by the Allen Institute for AI, a visionary institution founded by the luminary Paul Allen in collaboration with Microsoft.

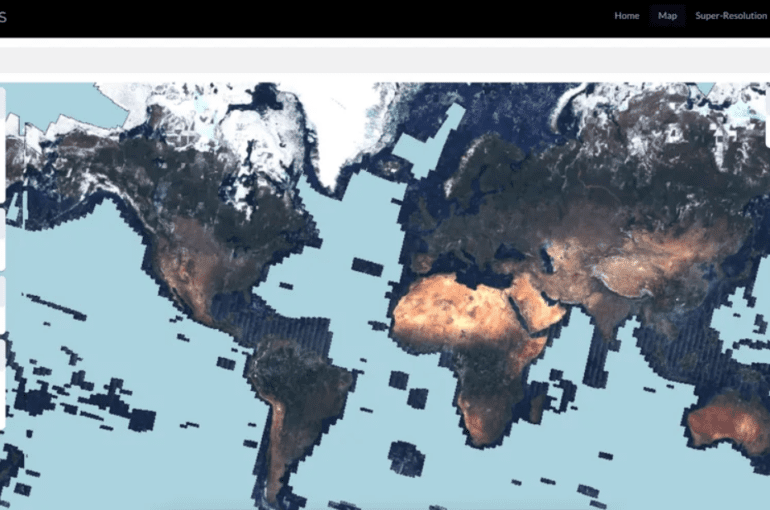

Diving into the mechanics of this technological marvel, Satlas ingeniously harnesses the omnipotent prowess of generative AI to enhance the clarity of space-captured images. While utilizing data sourced from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellites, which orbit high above Earth, Satlas employs a transformative feature aptly dubbed “Super-Resolution.” This innovative facet, steeped in the depths of deep learning models, impeccably fills in the intricate details that might otherwise remain shrouded in obscurity—manifesting in high-resolution images that unveil the concealed nuances of our world.

The initial focal point of Satlas lies in the realm of renewable energy ventures and the verdant canopies of trees that cloak our continents. This reservoir of dynamic data undergoes monthly updates, offering a comprehensive view of regions monitored by Sentinel-2. Notably, the purview encompasses vast stretches of our globe, sparing only the enigmatic reaches of Antarctica and the boundless expanses of open oceans.

In this visual tapestry, one can discern the sprawling landscapes of solar farms and the iconic silhouettes of onshore and offshore wind turbines. Yet, the narrative extends beyond the mere representation of infrastructure; Satlas also chronicles the metamorphosis of tree canopy coverage over temporal bounds. This profound insight serves as a lodestar for policymakers navigating the labyrinthine course toward climate and environmental objectives. Remarkably, the Allen Institute proclaims this as an unprecedented tool, graciously accessible to the public, unfettered by the shackles of subscription models.

Embedded within Satlas is an unparalleled demonstration of super-resolution technology on a global canvas—a testament to the meticulous craftsmanship of its developers. However, within the realm of innovation, imperfections are stepping stones to perfection. Satlas, akin to its generative AI counterparts, exhibits a tendency towards “hallucination” or, in more pragmatic terms, a minor shortfall in accuracy. Ani Kembhavi, the accomplished Senior Director of Computer Vision at the Allen Institute, aptly encapsulates this phenomenon. “Perhaps a building’s geometry is a rectangle, yet the model perceives it as trapezoidal—a whimsical misrepresentation.”

This disjuncture could arise from architectural disparities specific to distinct regions, evading the anticipatory grasp of the model. Similarly, the curious phenomenon of “hallucination” unveils itself in instances where vehicles and vessels materialize in locales envisioned by the model but far removed from reality. In essence, the model maps these entities based on the images underpinning its training.

The inception of Satlas demanded Herculean labor—teams at the Allen Institute meticulously sifted through a treasure trove of satellite images, painstakingly labeling 36,000 wind turbines, 7,000 offshore platforms, 4,000 solar farms, and quantifying the canopy coverage of 3,000 trees. This veritable opus served as the crucible in which the deep learning models were forged—imbued with the power to autonomously identify these features. Moreover, the saga of super-resolution unfolded through the model’s exposure to myriad low-resolution images of the same locales at distinct temporal junctures. These glimpses, in turn, enabled the model to prognosticate sub-pixel intricacies within the high-resolution vista it unfurls.

Anticipating the future trajectory, the Allen Institute envisions Satlas as a vanguard heralding a new era of comprehensive cartography. A future iteration envisions a map not just delineating geographic terrain but one capable of discerning the tapestry of crops adorning our planet’s surface. “Our endeavor was anchored in constructing a bedrock model for planetary observation,” Kembhavi declares with conviction, “a model ripe for meticulous tailoring to diverse missions. These AI-driven prognostications will be poised to empower scientists worldwide, facilitating the study of climatic shifts and other momentous phenomena that shape our Earth’s destiny.“

Conclusion:

The introduction of Satlas marks a pivotal step toward data-driven climate action. By amalgamating generative AI and satellite imagery, this comprehensive map empowers policymakers, scientists, and stakeholders to chart a more sustainable future. While some challenges persist, such as accuracy and “hallucination” concerns, Satlas showcases the potential of AI in climate research and inspires the development of novel solutions. As the technology evolves, businesses and markets in renewable energy, environmental monitoring, and agricultural sectors stand to gain significant insights, fostering innovation and informed decision-making.