TL;DR:

- Montreal writers, including Trevor Ferguson, express concerns over AI’s use of their literary works without consent or compensation.

- Authors Guild in the U.S. files a class-action lawsuit against OpenAI for alleged copyright infringement, with support from famous authors.

- Writers’ Union of Canada and Quebec Writers’ Federation consider similar actions to protect authors’ rights.

- AI’s ability to generate content threatens genre writers, making their work potentially replaceable.

- Authors already face financial challenges in the writing industry, making AI infringement even more impactful.

- Heather O’Neill and Rosemary Sullivan emphasize the violation of human storytelling and the need for legal measures.

- John Degen highlights the ongoing struggle to protect writers from technology companies.

Main AI News:

In the bustling city of Montreal, Detective Émile Cinq-Mars races against the clock to unravel mysteries and defuse potential car bomb threats lurking on its vibrant streets. Yet, behind the scenes, a different type of intrigue is unfolding as the world of literature collides with the realm of artificial intelligence (AI).

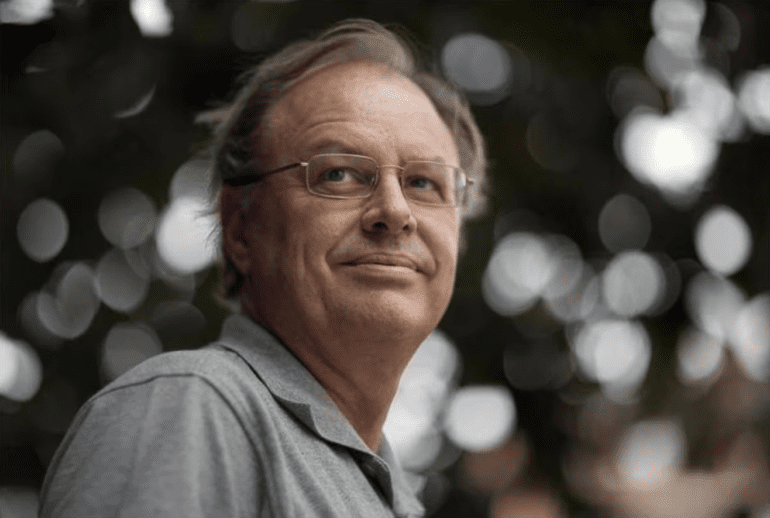

Renowned crime fiction writer Trevor Ferguson, known by his pen name “John Farrow,” has meticulously crafted hundreds of pages, weaving gripping tales where his detective protagonist takes center stage in the battle against Montreal’s underworld. However, shockingly, Ferguson recently uncovered that seven of his novels, alongside 183,000 other books, became unwitting subjects for AI training, with no compensation or consent sought from him. His characters, words, and plots have been harnessed by AI companies to generate narratives mirroring his distinctive storytelling style, giving rise to a troubling concern: Could Detective Cinq-Mars soon be solving mysteries in sequels penned by machine algorithms?

Trevor Ferguson’s dismay is shared by many Montreal writers who demand safeguards to protect their livelihoods from profit-driven companies exploiting their creative works. The Authors Guild in the United States took a bold step by initiating a class-action lawsuit against OpenAI, alleging systemic copyright infringement on a massive scale. Notably, acclaimed fiction authors such as George Saunders and Jonathan Franzen are at the forefront of this legal battle, though the outcome remains uncertain.

Adding their voices to this chorus of concern, the Writers’ Union of Canada and the Quebec Writers’ Federation (QWF) are contemplating similar actions, suspecting that pirated ebooks may have been the source of AI’s literary plunder. The fallout from this AI onslaught is poised to hit writers of “genre” writing genres, including mystery, fantasy, horror, and science fiction, the hardest. With a simple prompt, AI can potentially replace authors by conjuring new books, thus posing an existential threat to these creators.

This crisis arrives at a time when writers are grappling with dwindling incomes and a scarcity of writing opportunities to support their creative endeavors, rendering novel writing increasingly unfeasible. Trevor Ferguson himself endured years of odd jobs before achieving success with his detective series.

For author Heather O’Neill, the idea of machines generating poetry is a disturbing encroachment on the realm of human storytelling. The discovery that her words and metaphors were harvested by AI left her with a profound sense of violation. She passionately argues that this phenomenon perpetuates the misconception that artists should work for little or no compensation and that their creations are fair game for theft, undermining the intrinsic value of human experience.

The broader picture portrays artists who have long been asked to work for meager pay or none at all, further cementing the notion that their labor is expendable. This situation underscores the urgent need for legal measures to curb AI’s appropriation of creative material and safeguard the intellectual integrity of modern culture.

Rosemary Sullivan condemns this ongoing literary “robbery,” which threatens to disrupt the traditional channels through which authors and their works reach readers. As she points out, if AI can reproduce content online effortlessly, what incentive remains for authors to collaborate with publishers? Sullivan supports the ongoing lawsuit but emphasizes the necessity of enacting laws that target the root causes of piracy.

John Degen, CEO of the Writers’ Union of Canada, recognizes that the battle to protect writers from technology companies is an enduring struggle. He cites past instances like Google’s digitization of millions of books and an author’s ten-year fight with Amazon to remove AI-generated books falsely attributed to her as examples of this ongoing conflict.

Conclusion:

The growing concern among Montreal writers regarding AI’s unauthorized use of their work highlights the need for stronger copyright protections in the literary world. As AI threatens to replace genre writers and exacerbate financial challenges for authors, the market must adapt to ensure fair compensation and the preservation of intellectual integrity.