TL;DR:

- AI technology known as ‘Salmon Vision’ is developed in partnership with conservation groups, Simon Fraser University and First Nations to accurately count spawning salmon in British Columbia.

- ‘Salmon Vision’ AI achieved about 90% accuracy in identifying coho salmon and 80% accuracy for sockeye after analyzing over 500,000 video frames.

- This technology replaces laborious manual counting efforts, offering real-time, in-season information on salmon migrations.

- It enhances data quality, enabling better decision-making and governance for managing sockeye salmon populations.

- AI’s speed and efficiency provide a significant advantage over traditional methods, especially in the face of declining salmon stocks and climate change impacts.

- Collaborations with multiple First Nations aim to expand the use of AI technology in salmon monitoring across various sites in the near future.

- The project received funding from the British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund, a program by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Main AI News:

As wild salmon make their triumphant return to the rivers of British Columbia, an accurate count of their numbers becomes paramount for conservation efforts. In this critical endeavor, artificial intelligence (AI) emerges as a potent ally. Traditionally, the task of tallying spawning salmon has fallen to teams of volunteers or in-river video monitoring. However, a groundbreaking AI technology, known as ‘Salmon Vision,’ developed in collaboration with conservation groups, Simon Fraser University, and First Nations communities on BC’s North and Central coasts, is now revolutionizing the process.

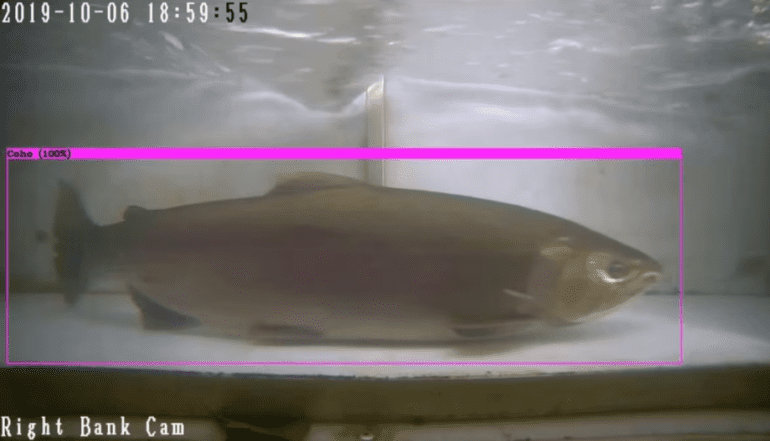

This innovative computer vision deep learning model has demonstrated exceptional accuracy, boasting a success rate of approximately 90% in identifying coho salmon and an impressive 80% accuracy in recognizing sockeye salmon. These remarkable results were achieved after analyzing more than 500,000 video frames. Will Atlas, a scientist with the Wild Salmon Center and the lead author of the report, elaborates on the role of AI in this endeavor: “The AI comes in the form of tracking and identifying every fish that swims past our video camera. Essentially, the AI replaces the laborious work of technicians, who would typically spend four to five months reviewing the video footage before providing a final count.“

The data sets for this pioneering project were obtained from weirs strategically constructed in the Skeena River watershed. Weirs, ancient First Nations devices resembling small, man-made dams, were originally designed for fish harvesting. However, during this pilot project, they were repurposed for monitoring and played a pivotal role in producing the report’s results.

Atlas emphasizes the next phase, which involves the widespread integration of AI technology into the field. This is particularly crucial due to the vast network of water systems in the province and the escalating impact of climate change, which renders accurate fish counts increasingly challenging and vital. Atlas states, “One of the most exciting aspects is that it will provide real-time, in-season information on salmon migrations. This data can significantly influence more precautionary and data-informed fishing decisions.”

William Housty, associate director for the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, eagerly anticipates the implementation of AI technology at a weir in the Koeye River, within the nation’s territories on the central coast of BC. He believes that AI will enhance data quality, leading to better decision-making and governance by the Heiltsuk Nation in managing sockeye salmon on their land. Housty states, “It’s an extension of our title and rights, granting us the ability to manage salmon systems and develop management plans based on accurate data with minimal margin for error.”

Over the past few decades, salmon stocks have witnessed a steady decline, accompanied by limited data for analysis. AI’s speed and efficiency offer a remarkable advantage, enabling data analysis at a pace unmatched by human capabilities. This timely information can be instrumental in safeguarding the struggling salmon population. Housty points out, “It significantly enhances our capacity as a nation and as field technicians. By employing AI in this work, our teams can divert more effort towards areas that were previously neglected due to time constraints.”

The Wild Salmon Center, in collaboration with the Pacific Salmon Foundation and multiple First Nations, envisions the widespread adoption of this transformative technology in the coming years. This ambitious endeavor was made possible through funding from the British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund, a program by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

A technician reviews computer vision images of salmon on Haida Gwaii territory. Funding from Fisheries and Oceans Canada has been used by a team of researchers to experiment with AI technology that has shown promise for its ability to accurately count and differentiate species of salmon in B.C. waterways. Source: Leah Honka

Conclusion:

The integration of AI technology in monitoring wild salmon stocks in British Columbia is a game-changer. It not only boosts accuracy and efficiency but also empowers First Nations with crucial data for improved salmon management. This innovation has the potential to reshape the conservation and fishing industry in the region, providing real-time insights to guide sustainable practices in the face of declining salmon populations.