TL;DR:

- Marshall Price’s jest leads to a groundbreaking experiment at Duke University’s Nasher Museum of Art.

- AI chatbot ChatGPT takes on the role of a curator in organizing an art exhibition.

- The experiment unveils a visually disjointed yet thematically cohesive exhibition titled “Act as if You Are a Curator.”

- ChatGPT’s ability to swiftly identify themes and artworks highlights its potential to assist human curators.

- However, the AI makes errors in inclusion, labeling, and descriptions, revealing limitations.

- ChatGPT’s cost-effectiveness at $10.71 raises questions about its role in the future of curation.

- AI curation is in its infancy, offering intriguing possibilities but requiring careful consideration.

Main AI News:

In a twist that resonates with the intersection of art and technology, Marshall Price, the Chief Curator of Duke University’s Nasher Museum of Art, jestingly suggested that artificial intelligence could curate their upcoming exhibition. Little did he know that this seemingly lighthearted remark would set in motion an intriguing experiment that is about to reshape the art world’s perspective on AI technology.

As the Nasher Museum faced the challenge of filling a gap in its fall programming schedule, its curatorial staff rose to the occasion. In an era where artificial intelligence is poised to redefine established roles across various professions, from military pilots to comedians, the team saw an opportunity to investigate the potential of AI in their own domain.

However, this experiment was no walk in the park. Marshall Price candidly shared that the team initially underestimated the complexity of the task, believing it would be as simple as inputting a few prompts. Over the past six months, the museum’s curators undertook the formidable task of teaching ChatGPT, a prominent chatbot developed by OpenAI, the intricacies of their profession.

The fruits of their labor will be unveiled in the upcoming exhibition titled “Act as if You Are a Curator,” which runs on Duke’s campus until mid-January. This groundbreaking event marks one of the initial forays into AI-curated art exhibitions, at a time when the museum industry is grappling with its evolving relationship with technology.

The question of whether the exhibition can be deemed a curatorial triumph remains open to interpretation. ChatGPT demonstrated its ability to identify themes and construct a checklist of 21 artworks from the museum’s collection, complete with placement instructions. However, it became apparent that the AI lacked the nuanced expertise of its human counterparts. The resulting exhibition was compact, with debatable inclusions, mislabeled objects, and inaccurate informational texts.

As Duke’s museum staff and researchers engage in a spirited debate over the exhibition’s quality, Marshall Price offered a candid assessment. He described it as an “eclectic show,” visually disjointed yet thematically cohesive.

The journey began with Mark Olson, a Duke professor specializing in visual studies, overcoming technical hurdles to fine-tune ChatGPT for the museum’s extensive collection of nearly 14,000 objects. Julianne Miao, a curatorial assistant, embarked on the initial “conversations” with the chatbot, instructing it to curate based on themes like dystopia, utopia, dreams, and the subconscious.

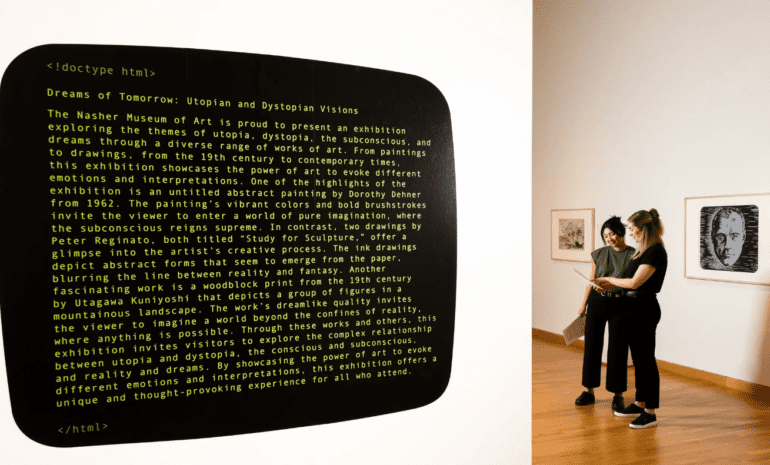

ChatGPT’s responses gradually evolved into the theme “Dreams of Tomorrow: Utopian and Dystopian Visions.” While the process paralleled a typical curatorial brainstorming session, the AI possessed the ability to swiftly sift through the entire collection and unearth artworks that human curators might have overlooked.

However, ChatGPT’s quirks and imperfections became apparent when it included objects seemingly unrelated to the chosen themes. For instance, the inclusion of stone figures and a ceramic vase from Mesoamerican traditions puzzled the team. Despite its questionable relevance, the AI brilliantly (or erroneously) titled them as “Utopia,” “Dystopia,” and “Consciousness,” making them suitable candidates for the exhibition.

These errors underscored the limitations of automating the curatorial process, prompting the team to reevaluate their use of keywords and descriptions in their cataloging systems. ChatGPT, powered by AI technology that predicts the next word based on extensive human-generated data, still falls short in handling intricate tasks like managing loans, scouring archives, and fact-checking.

While AI-driven curation remains in its infancy, it serves as a thought-provoking experiment that compels human curators to reimagine their approaches from a machine’s perspective. Previous instances, such as Romania’s Bucharest Biennale organized by Jarvis, explored the role of AI in artist selection, and projects like “The Next Biennial Should Be Curated by a Machine” employed AI tools to satirize conventional art discourse.

Roderick Schrock, director of Eyebeam, emphasizes that AI curation has yielded simplistic results thus far, cautioning against using chatbots to dazzle with technology rather than fostering meaningful engagement.

In the Nasher exhibition, ChatGPT generated descriptions for selected artworks, crafting an introductory text of approximately 230 words. Despite its shortcomings, the AI’s speed in drafting exhibition content and suggesting lighting arrangements proved valuable. It shed light on the importance of reviewing and correcting human errors within the museum’s catalog.

While the curatorial team’s reactions to the experiment vary, it’s evident that ChatGPT’s cost-effectiveness plays a pivotal role in their perspective. Developing their version of ChatGPT cost a mere $10.71 in technology expenses, making it easier to forgive its mistakes, provided human curators remain in the loop.

Large institutions, for the time being, are not rushing to embrace A.I.-curated exhibitions, but they closely monitor experiments like the one at the Nasher Museum. The consensus remains that automated curating, drawing from existing data, may not bring revolutionary insights but instead reflect what already exists in the art world—an echo chamber of familiarity.

For the exhibition, the A.I. chatbot selected 21 artworks from the museum’s collection of nearly 14,000 objects. Source: Cornell Watson

Conclusion:

The foray into A.I.-driven curation at the Nasher Museum of Art demonstrates the technology’s potential to assist human curators in swiftly identifying themes and artworks. However, the experiment also underscores the importance of addressing limitations such as inclusion errors and the need for human oversight. The cost-effectiveness of AI in this context raises questions about its role in the market. While AI curation remains in its early stages, it prompts the art industry to explore new ways of enhancing the curatorial process with technology while ensuring the preservation of human expertise and creativity.