TL;DR:

- Prominent Australian authors, including Peter Carey and Helen Garner, discovered their works used without consent in training AI.

- Books3 dataset, a repository of pirated ebooks, is revealed as the source for AI training, sparking outrage among authors.

- Legal battles ensue as authors seek redress against tech giants like OpenAI and Meta for alleged copyright infringement.

- Generative AI poses a substantial threat to authors’ livelihoods, flooding the market with inferior content.

- Authors face challenges in pursuing litigation due to financial constraints.

- The Australian Society of Authors advocates for stronger copyright protection and negotiations with the tech sector.

- The situation underscores the need to redefine ethical boundaries and enhance legal safeguards in AI development.

Main AI News:

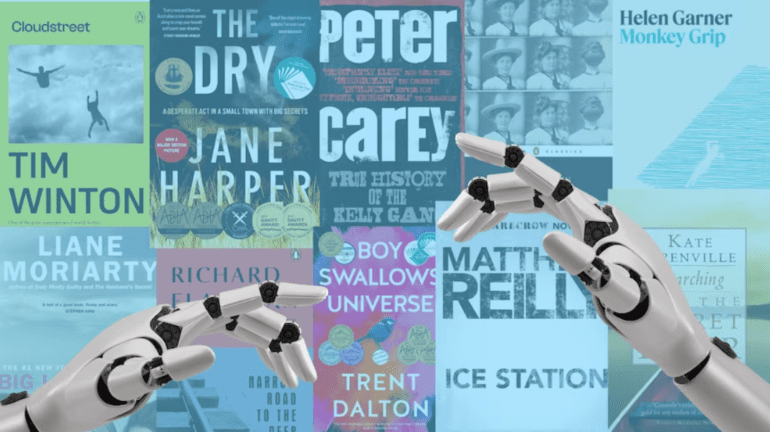

The Australian literary world is abuzz with controversy as prominent authors, including Peter Carey, Helen Garner, Tim Winton, Jane Harper, and Miles Franklin, find their works embroiled in a Silicon Valley-based AI scandal. The heart of the matter revolves around the Books3 dataset, an extensive collection of pirated ebooks that have unwittingly served as the training ground for cutting-edge generative AI systems.

In an era where AI systems voraciously consume vast volumes of textual data scraped from the internet, the lack of transparency regarding the content used for training generative AI has left authors in the dark. Olivia Lanchester, CEO of the Australian Society of Authors (ASA), succinctly encapsulates the issue, stating, “[We know] AI systems are trained by ingesting vast amounts of text … scraped from the internet. But the lack of transparency over what has been used to train generative AI means that authors haven’t known whether their works have been used.”

This revelation has stirred a maelstrom of emotions among affected authors. They are not only dismayed but also outraged to discover that their intellectual property has been appropriated without consent. Lanchester notes, “We have been receiving phone calls and emails from Australian authors who’ve been dismayed and outraged to learn that their works have been appropriated without their permission.”

The Books3 dataset, which has now come under the spotlight, features literary gems not just from Australian authors but also from globally acclaimed wordsmiths like John Grisham, Colleen Hoover, and Stephen King. This revelation has raised important questions about the ethics and legality of AI training data.

In September, The Atlantic published a tool to search the Books3 dataset, shedding light on the author information associated with its contents. The creator of Books3, Shaun Presser, defended his dataset as a high-quality resource intended to empower independent developers, allowing them to compete with tech giants like OpenAI.

The moral compass of the tech industry is called into question, as renowned Irish-born crime writer Dervla McTiernan, whose bestselling novel “The Ruin” is among the pirated works, condemns this as outright theft. McTiernan asserts, “It’s outright theft. People who stole all of these books … did it for the purposes of making money.” She further contends that the companies behind these AI systems were well aware of the pirated nature of the dataset.

Professor Toby Walsh, Chief Scientist at UNSW’s AI Institute, raises a valid point by questioning the need for using copyrighted works for AI training when a plethora of public domain texts could suffice. He criticizes the cavalier attitude of Silicon Valley towards intellectual property, stating, “It’s typical of the cavalier way that people in Silicon Valley treat people’s intellectual property.“

Lanchester echoes this sentiment, emphasizing that AI developers could have sought licenses or used public domain content, instead of “ingesting copyright works without seeking permission.” The disregard for copyright laws, she contends, overlooks the real cost of creation and the critical role licensing plays in authors’ livelihoods.

The repercussions of this AI overreach are not confined to ethical debates; they have entered the realm of legal battles. Tech giants like Meta and OpenAI are facing multiple lawsuits in the United States over their alleged unauthorized use of authors’ work. Authors Mona Awad and Paul Tremblay, along with other notable figures, have taken legal action against OpenAI, accusing the company of “systemic theft” and “mass copyright infringement.”

The ongoing legal battle hinges on the interpretation of “fair use” concerning the use of copyrighted material for AI training. As Professor Walsh aptly notes, “This is a new way of using people’s copyrighted material, and the courts have yet to decide whether it’s fair use, whether it’s within the bounds of the law or not.”

Generative AI poses a formidable threat to authors’ livelihoods. Flooded markets with inferior AI-generated content not only hinder discoverability for professional writers but also lower the overall quality for consumers. Authors like McTiernan worry that AI tools, though presently regarded as “bad writers,” may evolve to replicate contemporary authors, directly competing with original novels.

For Australian authors, already grappling with a precarious occupation, the road to legal recourse is fraught with challenges. With limited financial means, many are unable to pursue litigation against tech giants. This stark power imbalance raises questions about accountability and the need for stronger protections for authors.

ASA intends to advocate for authors and negotiate licensing solutions with the tech sector, while authors are closely monitoring the outcomes of lawsuits brought against AI behemoths by the Authors Guild and individual writers. The complexity of legal and jurisdictional issues surrounding this matter adds to the ongoing uncertainty.

Conclusion:

The Books3 dataset scandal serves as a clarion call for reevaluating copyright protection in the digital age. It highlights the urgency of defining ethical boundaries in AI development and strengthening the legal safeguards that protect authors’ intellectual property. As the influence of AI continues to grow, it is imperative that the tech industry recognizes and respects the value of authors’ creative contributions. Only through a harmonious balance between innovation and authorship rights can the literary world thrive in this evolving landscape.